The assertion that women have had a lower presence in scientific research than men is not new. We have evidence that women have been clearly underrepresented in experimental sciences, engineering and medicine, among other fields of knowledge.

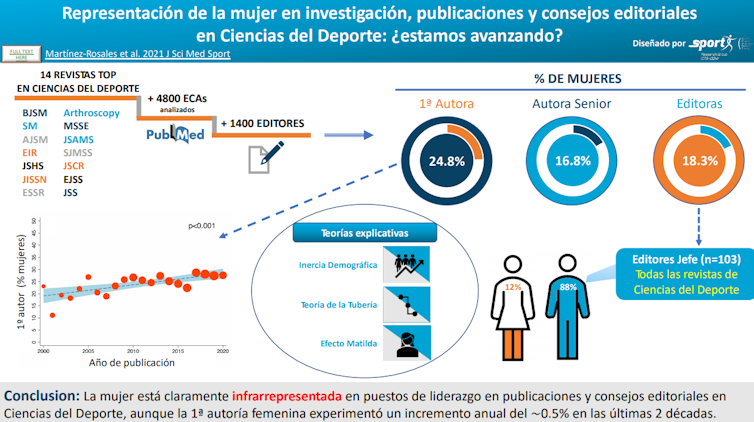

A study by the University of Almeria now shows that, in the last 20 years, the presence of women in leadership positions in sports science research has been, at times, marginal.

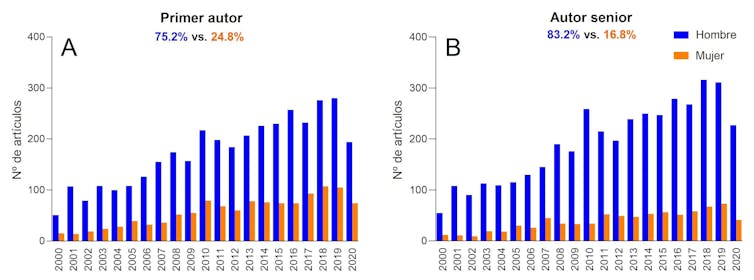

At this study The first and last authors (leadership positions) of almost 5,000 first-level scientific articles were identified as male or female. The results showed that only one out of four articles were led by women in first authorship.

This low representation was even more accentuated in positions of greater responsibility, where only one in six articles had a woman as the last author. Given that this last position is almost always occupied by the leader of the research group or the principal investigator of the project, it seems clear that sport science research in the last two decades has been predominantly led by men.

Join and bet on evidence-based information.

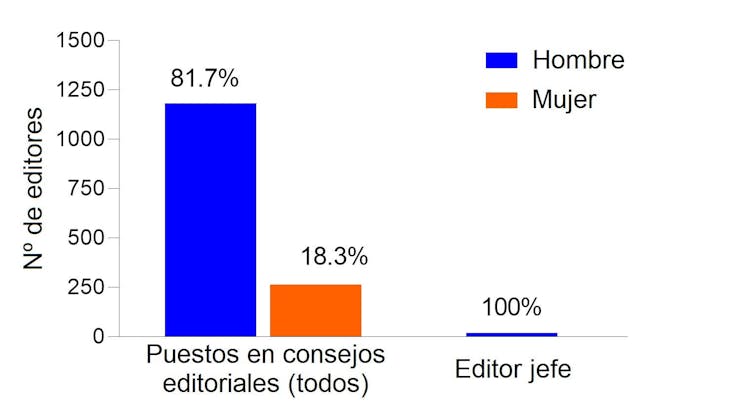

This same analysis by gender was conducted with more than 1,400 editorial board positions in 14 of the world's top journals in sports science. It may be overwhelming to find that 82 % of the editorial positions are held by men.

But it may be even more shocking that, when all the editor-in-chief positions of the 85 most internationally prestigious journals in the field were analyzed, women held only 12 of the 103 available positions (a 12 %).

Editors-in-chief are responsible for making the decisions that advance science, as they decide on the topics that are relevant, the articles to be published, etc. With a 12 % of representation, it can be stated that women have had virtually marginal influence in these decisions and that there is ample room for improvement.

What are the repercussions of the low presence of women leading science?

The first consequence of the scarce presence of women in research and editorial processes is the lack of diversity and perspectives in decision-making. This greatly reduces the variety of research topics, such as those related to women's sports, which have been largely ignored by science.

For example, today we know that the physiology of women in sport is clearly under-researched. With the professionalization of women's sports, coaches and physical trainers have great difficulty in scheduling elite women's training based on scientific evidence from studies on men.

Also women editors have been associated with a more thorough and rigorous editorial process.This could indicate that a more equitable composition of women and men could increase the quality of scientific research in this area.

Why this low presence of women?

Some theories explain this lack of female leadership in sport science research. One of them is called "demographic inertia". This theory suggests that the people who were working in the field 20 or 30 years ago are the ones who occupy the leadership positions today.

Given that sports science is a field of study that has traditionally been heavily male-dominated, this theory can explain much of this data. For example, of the 3 866 people who graduated in Spain in sports science in 2014, only 21 % were women.. For this reason, it seems difficult to think that it is possible to reverse these differences in the short term.

The pipeline theory explains that at each stage of education, women are lost and at the end of the pipe (in the case of science, graduate and postdoctoral studies) there are few women left who aspire to leadership positions.

But why are women being lost along the way? It is possible that the lack of role models plays an important role in attracting female talent in sports science. The messages that society implicitly conveys to women from an early age may also play a role.

A University of Chicago study found that when high school students interviewed professionals about possible jobs, girls received twice as many messages related to the importance of having a work-life balance as boys did. Undoubtedly, receiving such subliminal messages on an ongoing basis through the family, the educational system, and the professional world can deter women from pursuing a career in sports science.

The Matilda effect describes how women's merits receive less recognition than men's merits. This is the theory that best identifies with gender inequalities. There are clear examples of the Matilda effect in scientific research. In 1997, a study showed that women who applied for a research grant from the Swedish Medical Research Councilneeded 2.5 times more merits than men to compete on an equal footing..

However, the extent to which the Matilda effect has had a significant impact on the sports science field is currently unknown. Only further research can determine exactly what mechanisms have led to these low percentages of women in leadership positions.

Reversing the trend?

The good news is that the percentage of women as first author increased by 0.5 % annually from 2000 to 2020. This is an encouraging development that, if it continues, could even out the balance in the coming decades.

What is not clear is whether this increase is sufficient or whether it is being too slow.

Knowing that there has been no change in the presence of women as senior authors or as authors in general, it is important to continue working so that this trend can be extended to positions of greater responsibility in the coming years.

What's next?

This study highlights for the first time the low presence of women in sports science and corroborates the low representation of women in science. Now we need two things: first, to understand why we are like this; second, to look for mechanisms to increase the attraction of talent and female presence in this field of knowledge.